Copy make

(2015-ongoing)

Copy make is a demonstration video about the physicality of sound and proposes new methodologies of working relationships between composer and performers in an open and visually centred collaborative approach. You can read further about this project here in a peer-reviewed paper in Leonardo Music Journal, Volume 30, 2020. The video-essay below explores an area I felt was lacking in contemporary art music, that being, the lack of engagement with ‘somatic video notation’ or ‘video gestural notation’.

Not many musicians or institutions know how to cater for something like this but that can be good as it can undermine existing power structures, be the impetus for new research, and influence change. It’s not typically taught at Universities so there’s a gap in the knowledge, but I think over time it will become more widely accepted as people start to conceive of what it is, its value, and its placement within a historical context. Words like ‘graphic notation’ and ‘animation notation’ are not adequate in explaining this approach. But they are good examples of terms that were once on the fringes that are now more broadly used, especially as visual software has become more accessible and easier to use.

I wanted my process to be somatic, embodied, people-centred, collaboration focused, engaged in; new modes of learning, relational aesthetics, perceptual openness, and abstract thinking, all within a new visual language.

Copy-make came about in a workshop where the premise was the preconditions of music, ‘music without sound’, and ‘composition beyond music’. My response was to make visible the invisible world of music through a display of its gestural processes. This allowed for a transference of a diverse array of parameters involving; rotation, closing, expanding, roughening, smoothing, demarcation, recursion, inversion, punctuation, dynamic change, velocity, and duration.

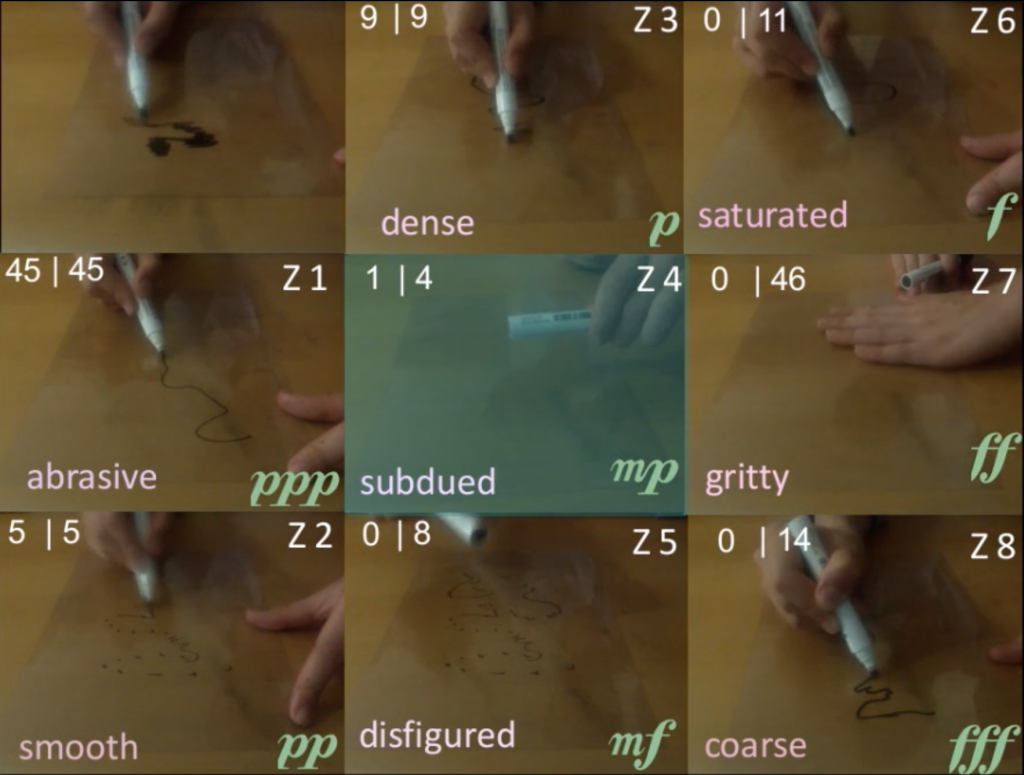

Sound and movement are recorded on a glass surface to be used as a multi-screen video score for musicians to use with an instrument or sounding object. Text, numbers and symbols are written over videos containing gestural movements – a technique called digital annotation that has been used in the field of dance and anthropology. The emphasis is on the line-semantics of the performers movements. A gestural matrix allows for multiple points of focus for the performer to reiterate, interpret and retrace actions within a given frame (outlined here using yellow tape). This project was intended to be sound-based, but there is scope for it to be explored within a choreographical context. The video theorises potential uses of this way of working that could have multiple performance outcomes. It is a platform for experimentation and for realising a fixed work, and is open to anyone who wants to discover its possible uses.

Copy-make explores the embodied process of correspondence as a compositional tool and framework for thinking about gesture in music. I use correspondence in an ongoing inquiry carried out through collaborative relationships and between: the body and the music instrument; a sounding musical gesture and the nonsounding; and visual-aural and haptic-gestural relations that are part of the scoring and rehearsal process. The documentation of movement and its correspondence renders my scores somewhat like somatic maps. I use the term “line-mapping” to explain this process of discovering, transcribing, notating and transforming gestural pathways.

Cross-modality in a music process

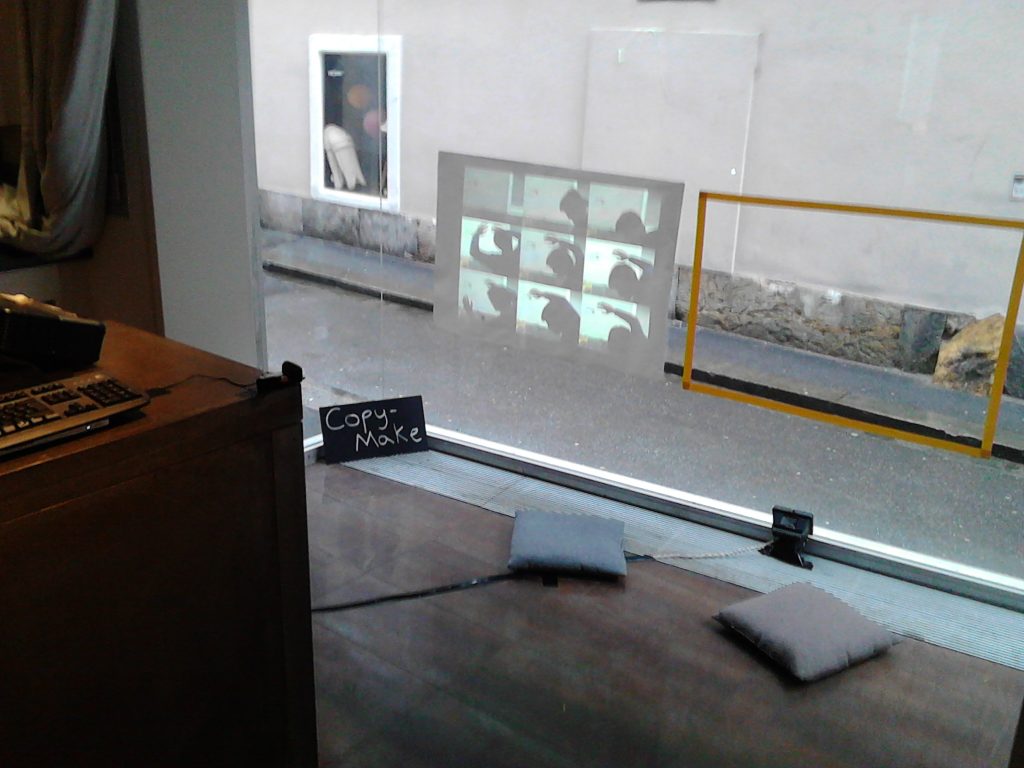

As a method of scoring for the body, I developed an installation, Copy-make, that focuses on the physicality of sound and proposes new methodologies of working relationships between composers and performers.

A camera and a microphone are positioned facing a glass window surface. Performers are invited to make movements and sounds on the glass using either a musical instrument or a sounding object, or by tapping and rubbing on the glass itself. The recording devices capture short looping videos that are projected onto a screen to the left. The performer uses these videos as a score to inform their gestural actions. The emphasis is on the line-semantics generated by the performer’s movements that are placed within a multigestural matrix. This allows the performer to see and interpret their lines and then remake, reiterate or retrace these actions within the given frame The performer is instructed to make corresponding gestures by superimposing complementary (or contrary) lines.

In this work, gesture is conveyed through a cross-modal medium, where the body is used to transmit musical instruction. The duration, shape, rotation, posture, location and speed are all used to inform gestural choices. Sound is partly indeterminate but does have equal weight in the composers’ and performers’ decisions.

When I use the term cross-modal, I am referring to the sensory modalities: the aural, the visual, the motor, the tactile and the imagination, and how these physical or perceived processes can correspond within the work. In Listening, Jean- Luc Nancy states: “Nothing is said of the sonorous that must not also be true for the other registers” (Nancy, 2007). Copy-make then offers a platform for this dialogue between the senses and demonstrates that our sensory registers have an immense capacity for corresponding. It challenges musicians to think through a kinesthetic-based methodology of composition within a collaborative environment. I also reference Gritten, King and Welch, who suggest “that musical gestures are cross-modal and that gestures include non-sounding physical movements as well as those that produce sound” (Gritten et al. 2016).

The installation becomes a performance, with audiences watching as the performer constructs the work. The performer is not simply imitating the videos but goes through a rigorous process of transforming them, internalizing them and superimposing complementary lines of movement. The work offers a playground or sketching process for generating ideas. It allows the performer to build an archive of music gestures and then make choices to correspond with it: moving under their line, over it, with it, or against it, smoothly or dynamically in a wavy motion. Copy-make can be adapted and customized in myriad ways, depending on the instrument(s) being used and the composers’/performers’ relationships and how they envision the work.

This work brings to the foreground the cross-modality of music and the framing and mapping of the delicate nuances of touch. Think of musicians’ hands on their instruments or even how sound vibrations touch cochlear hair cells before becoming signals in the brain. In this work, the body transmits the score.

The work aims for an inversion of eye-ear relations, making visible the invisible world of music. The use of videos also makes visible an unfolding sonic-gestural process. What is seen, heard and interacted with in the score are processes including but not limited to recursion, inversion, rotation, closing, expanding, roughening, smoothing, demarcations, punctuations, dynamic changes, velocities and durations.

Video in Music and Dance Practices

The discussion of the visual and choreographic perspectives in my music can be contextualized through absurdist instrumental pieces such as those by Mauricio Kagel. Kagel produced a video score out of his film Ludwig van (1970), which consists of staged footage inside Beethoven’s music studio, and the performers play musical fragments in the sequence of their appearance on screen. Some score fragments are missing clefs, key signatures and tempo, with different degrees of clarity from the camera’s lens, and some fragments are upside down. The piece functions differently from the video score in Copy-make, concerning the transference of a line of movement on screen to a location on an instrument’s surface. However, both pieces include similar ideas of flipping, inverting and stretching musical fragments through visual representation.

Jennifer Walshe’s work dirty white fields (2002) uses video, images and text as a compositional process. Walshe provides audio and video clips and poetic descriptions of sounds to establish an idiom of what an imagined scene looks like, feels like, sounds like, smells like, etc. The performer then uses this to make specific technical instrumental choices. Similarly, Copy-make sets up a specific multisensory context for the performer to mediate their performance.

A video score was used as part of the process of Forsythe’s work Alien:a(c)tion (1992) involving scenes taken from the film Aliens. Velocities, orientations and directions of the actors in the film are used as directions for movement by the performers—similar to Copy-make. Images are also broken down into words and letters, where each letter has its own semantic meaning (for example, a cat in the video would represent the movements associated with the letters C, A and T).

Such works invite performers and audiences to open up their senses and engage the body. They are novel methodologies where video media is codified and actualized by a performer, a process that is sometimes hidden from the audience. It encourages those involved to look, to listen and to enter a state of reflection and kinesthetic empathy, all of which become methods for influencing the outcome of a performance.

References

A. Gritten, E. King and G. Welch, New Perspectives on Music and Gesture (Abingdon, U.K.: Routledge, 2016) p. 6.

Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening (New York: Fordham Univ. Press, 2007) p. 71.

Daniel Portelli, Music gesture and the correspondence of lines: Collaborative video mediation and methodology. (Leonardo Music Journal and MIT Press, 2020) Vol. 30.

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/764933/summary

Nikos Stavlas, Reconstructing Beethoven: Mauricio Kagel’s Ludwig van (Ph.D. thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London, 2012) p. 90.

John Lely and James Saunders, “Jennifer Walshe, dirty white fields (2002),” in Word Events: Perspectives on Verbal Notation (New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2012) pp. 366–376.

Michèle Steinwald, “Methodologies: Bill Forsythe and the Ballett Frankfurt by Dana Caspersen,” Walker Art Center Magazine (9 March 2007): www.walkerart.org/magazine/methodologies-bill-forsythe-and-the-ballett-frankfurt-by-dana-caspersen (accessed 5 March 2020).